“Yet when I surveyed all that my hands had done and

what I had toiled to achieve,

everything was meaningless, a chasing after the wind;

nothing was gained under the sun.”

(Ecclesiastes 2:11)

Leo Tolstoy’s story, the Death of Ivan Ilyitch, tells of a man who is coming to his end.

For some time, Ivan has tried to convince himself he will recover, and that the burning pain within his belly will soon fade like any other minor illness. Only as it becomes inescapably clear that death is near does Ivan face the question he has been ignoring all his life: Has he lived well, sought worthwhile goals? Or, was it possible that he had spent himself on selfish and meaningless pursuits?

Other members of the Russian judiciary had no doubts about him. Ivan climbed the political ranks rapidly. He owned a well decorated home in a popular neighborhood. His wife was fashionable, his child healthy, and Ivan himself generally quite well liked. His fellow judges may have pondered what impact Ivan’s departure would have on their own career advancement, but there was no doubt in their minds: Ivan was a success.

But Ivan was not so sure. His body now throbbed with a pain the doctors could do no more than mask for a few hours at a time. He lay upon his couch, reviewing his life’s journey. And with an ache even worse than the physical pain, Ivan begins to see, “It is as if all the time I were going down the mountain, while thinking that I was climbing it. So it was. According to public opinion, I was climbing the mountain; and all the time my life was gliding away from under my feet.”

For a time, Ivan succeeds in battering back this horrible realization. He reminds himself of his many accomplishments, of his admirers and the status of his position. It is not long, though, before the thought roars back into his mind, “Wrong! All that for which thou hast lived, and thou livest, is falsehood, deception, hiding thee from life and death.”

It is only here, at his end, that Ivan has realized the awful truth: He as charted his life by false measures of success.

“And as soon as he expressed this thought,” Tolstoy explained, “his exasperation returned, and, together with this exasperation, the physical, tormenting agony; and, with the agony, the consciousness of inevitable death close at hand…”

Well over a century after it was written this tale still haunts those who read it. The impact is not merely a result of well-written prose. It is because readers know that the story describes countless men and women in every age – people realize, only as their end draws near, that the light by which they had set their lives was not, after all, the North Star.

Perhaps we have imagined that feelings of uncertainty and dissatisfaction in the midst of what appears to be towering success were strictly a present-day phenomenon. History allows no such illusions.

“The true worth of a man

is measured

by the objects he pursues.”

(Marcus Aurelius)

It was nearly three millennia ago that one of ancient Israel’s greatest kings, drawing to his end, recorded final reflections in the book of Ecclesiastes. The monarch life had overflowed with stunning accomplishment, vast knowledge, and tow-curling pleasures. After reviewing all he achieved, however, his conclusion sounds disturbingly similar to that of Ivan Ilyitch: “Yet when I surveyed all that my hands had done and what I had toiled to achieve, everything was meaningless, a chasing after the wind…”

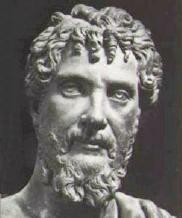

Centuries later,

Centuries later, the Roman emperor Septimus evaluated his own life with much the same words. “I have been everything,” he recalled, “and it is nothing.”

It seems all three of these lives could be summed up quite well in the expression of Britain’s Sir Mick Jagger: “I can’t get no satisfaction.”

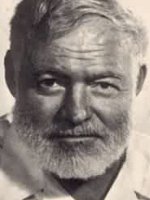

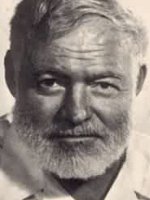

Ernest Hemingway

Ernest Hemingway is heralded as one of the greatest writers in the history of the English language. He received the Pulitzer Prize in fiction and the Nobel Prize in literature, drawing writing material from his own grand exploits as a war correspondent, adventure traveler, and bona fide Don Juan. Hemingway lived his life in a way that would be the envy of any person who had bought in to the values of our modern society. Hemingway was known for his tough-guy image and globe-trotting pilgrimages to exotic places. He was a big-game hunter, a bull-fighter, a man who could drink others under the table. He was married four times and lived his life seemingly without moral restraint or conscience.

Said, “I live in a vacuum that is as lonely as a radio tube when the batteries are dead, and there is no current to plug into.”

Then, one sunny Sunday morning in Idaho, he pulverized his head with a shotgun blast.

Marilyn Monroe

Marilyn Monroe became an actress known the world over – a symbol of sexuality and beauty for her generation and beyond. In the midst of her career, she opted for an early exit, downing a month’s worth of sleeping pills.

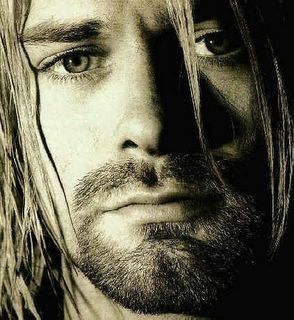

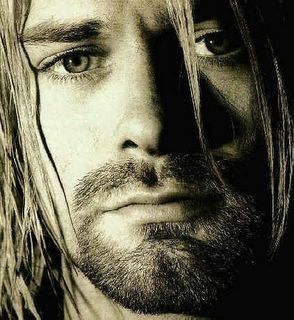

Kurt Cobain was considered by many to be the voice of his generation. His album Nevermind sold ten million copies in the United States alone and was heralded in 2002 by Rolling Stone as the second greatest record of all time. At 27, he overdosed on tranquilizers in an apparent suicide attempt. A few months later, in a cottage overlooking Lake Washington, he aimed a shotgun at himself and pulled the trigger.

Kurt Cobain was considered by many to be the voice of his generation. His album Nevermind sold ten million copies in the United States alone and was heralded in 2002 by Rolling Stone as the second greatest record of all time. At 27, he overdosed on tranquilizers in an apparent suicide attempt. A few months later, in a cottage overlooking Lake Washington, he aimed a shotgun at himself and pulled the trigger.

Admiring glances from people around you … a reputation for eloquence … articles written and books published … promotions and raises … invitations to the right homes, the right parties. No doubt, lives fixed in pursuit of such successes gratifies for a time. But if serving as the North Star – the ultimate end and goal – they will not lead true.

The suicide note Cobain left behind may have rambled, but it did not fail to depict the place to which his success had led. No doubt, it spoke for many other renowned-yet-failed communicators as well. “I haven’t felt the excitement of listening to as well as creating music along with reading and writing for too many years …” he wrote. “I’ve tried everything within my power to appreciate it, and I do. God, believe me I do, but it’s not enough…”

Most of us will never reach the heights achieved by fabled figures like Hemmingway, Monroe, or Cobain. Their endings merely provide us clues, hinting that even the smaller successes we seek may not, after all, bring the satisfaction we often imagine.

In time, most everyone comes face to face with this reality. A man in a California firm watched as a fifteen-year company veteran was given a termination notice and asked to clear out his deck. Bewildered, the fellow placed his personal effects in a box and said goodbye to colleagues he considered friends. By afternoon, his desk was filled by a newly hired manager, who picked up where its prior resident had left off. If what defines my life is measured in sales records, pay increases, or promotions, realized the man who had observed the seamless replacement, I’m lost.

Ponder...

Why are so many super-stars lives seemingly falling apart and hits the rocks of despair like those looked at above?

Interestingly enough, our culture is still enamored by these personalities. Magazines rave about which one is the hottest, sexiest, richest, and the most popular with the people. Talk Shows, Tabloids and Entertainment Programs love to reveal the deep, dark and dirty of their personal lives – scams, scandals, affairs, divorces, pregnancies, just to name a few. The ironic thing is, many of us are not only drawn to get the scoop, deep down inside we still long to be like them either in real life or the pseudo lives they lead on the big screen.

Regardless of fame and fortune, would one logically equate these types of internal realities, like the one’s depicted above as true success? Probably not, yet why has our culture (and perhaps we ourselves) become enchanted into living as if it really were true success?